A roll of film can be a time capsule of moments and forgotten memories. Precious, pointless, beautiful or ugly. Most of them would pass by unnoticed, forgotten in time like fleeting thoughts. Like so many memories, some pictures may not reveal their true depth of meaning until enough time has passed.

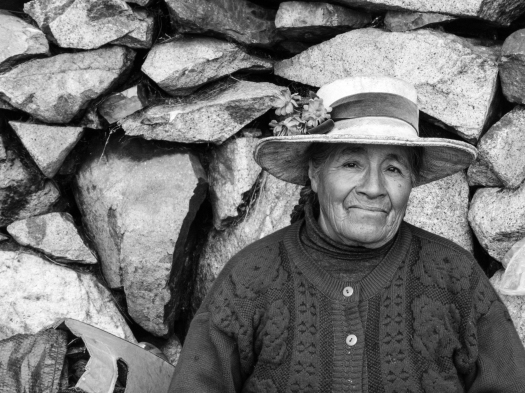

Photography lets you look at the world with different eyes. When I’m wandering around without a camera I find myself framing things in my mind’s eye. Looking at the space between objects and buildings, observing the world in more detail. Looking closer for beauty or interest in a way I wouldn’t have before. Lines in a freshly harvested field, dappled light cast between the leaves of a tree, the wrinkles of an old person’s face. Light takes on new meaning, colour becomes more true, lines and shapes give a simple scene more depth.

Autumn used to feel melancholic, that sense of going back to school while leaves wither and fall. An air of decay that brought a shudder to my bones at the prospect of the coming darkness of winter. Now it’s about the colours and vibrance that contrast the seasons, as leaves turn to orange, brown and red. It’s turned from a season to loathe to a season to love. Where as winter is no longer about long nights and short days but about long shadows cast by the low winter sun. Stark blue skies and the crisp beauty of a morning frost. The simple minimalism of a snow filled scene.

A couple of years ago my brother gave me an old Canon film camera for Christmas. It was heavy, solid to the touch and the clunk of the mechanism had a satisfying sound. The first roll I took was all but ruined by light leaks. I took it apart and replaced the light seals. I bought a roll of film and took it out in London one weekend to fire off some test shots. But having just moved to the big city at the time I was broke, so when I finished the roll I took it out of the camera, put it in a drawer until I could afford to develop it and forgot about it.

Six months later I discovered the roll again and got it developed. It’d been so long since I’d used it and I’d never seen or even thought about the shots I’d taken. Not since those split seconds that’d I’d looked through the view finder and opened the shutter. I picked up the CD and the contact sheet at the shop, prints seemed unnecessary. Looking over the sheet I remembered what I’d taken. A street entertainer in Covent Garden, the Millennium Footbridge and St. Paul’s, some shots of the Thames. They looked great, clear and crisp with a depth I’d not found with digital. But the last shot I couldn’t quite make out. It was different from the others, dark, taken in low light. I had to wait until I got home to load them onto the computer and have good look.

It was a plate on a table, some chicken bones and bits of left over food. I realised what it was as the memory came back into focus. It was a finished plate of food that my friend Jim Disney had cooked for me the last time I’d seen him on the boat he lived on with his girlfriend, Sarah, at Poplar Dock. I could make him out in the background, his trademark flannel shirt and tiny hands blurred in the background as he did the dishes. I’d taken it as a quick test to see how the camera operated in low light, a throwaway shot, not remarkable at all. Under any other circumstances I’d have deleted it.

The meal was chicken roasted in the oven in a baking dish with onions, tomatoes, herbs and chorizo. I remember Jim enthusing about the chorizo as we bought the ingredients in the shop earlier that day. He’d wished he could buy the oil that comes from it when it cooks by the bottle to add to sauces and marinades. I’d recently started eating meat after eight years without, so it was the first time that Jim had cooked me any. We used to live together in Leicester five or six years ago. Jim was superb cook. He’d make a big roast dinner every Sunday for the four of us who lived at Fosse Road South. He’d bumble around in the kitchen all day in his dressing gown, looking like a mini hairy Jesus with his beard and long curly locks. I’d get a ten minute warning so that I could come and cook some veggie sausages to eat with the veg. He’d knock on my bedroom door, “Joseph, time to cook your not sausages,” he’d say. He’d wait by the cooker with his ear to the pan, a hilarious grin on his big moon face. Then he’d nod in time to the clunk-clunk sound of the frozen meat free bangers hitting the surface of the pan.

He’d mock me, it was his way. But he cared. He once announced with glee that he’d put fat from the roast in the Yorkshire pudding mix. His face dropped as the words tumbled out and he realised what he’d done. “I feel guilty now,” he said before rushing around the kitchen to make a fresh set of meat free Yorkshires.

When I stayed with him in London on the way back from Peru two years ago he cooked veggie burgers in my honour. And it was an honour. He was religious about eating meat. When we lived together I’d have to wait for him to go out to cook a veggie meal for the house or he’d start getting jittery. I’d tried cooking veggie burgers myself countless times. I never got it right. The consistency was always wrong, either too sloppy or crumbly. Jim nailed it first time.

That night I took the photograph, he saw me to the gate of the marina. We had a hug and said goodbye. “You’ll have to come round for a roast next time, Joe,” he said.

A month or so later I was supposed to go over for a Sunday roast. I sent him a text that morning but he didn’t reply. When I called him his phone was off. Then I got the call. He’d had a heart attack that morning. He died a few days later.

The day he left us I met my friends, Jo, Steve, Zak and Danielle on the South Bank of the Thames. Some of us had finished or been excused from work early and converged to share our grief. We’d all stayed with Jim at Jo’s house on Fosse Road South at some point or another. Jo and Steve for many years. I arrived first and sat on a bench under the shade of a tree. It was a hot sunny day in May, the South Bank was packed. People milled around enjoying the weather, tourists, couples, buskers, a group of French school children on a trip. They stood around laughing and smiling, sitting on the grass drinking beer, eating picnics. I looked at the sunlight shining through the leaves of the tree. The smiling faces of the people around. The lines on the face of the old man sat on the next bench. None of it seemed real, like the world had just changed in some profound way. Everything seemed meaningless. I had a sudden surge of anger. Jim was just forty-years-old. How unfair and cruel it was that he wouldn’t be able to sit, like I did, and observe the world on a sunny day. Or feel the sun on his back and the light breeze on his face. Nothing made sense anymore.

The others arrived and we hugged, cried and told stories of Jim. We laughed at the memories. His wild adventures and hilarious turn of phrase, his belligerence, vulgarity and self deprecation. It felt like a family in that house, and Jim was like my little big brother. He could make me laugh from the belly up, with just a look from his cheeky face and pale blue eyes. His humour made me feel like a child. He was handsome, cool, hilarious. A comedian and a rockstar. I’m not ashamed to admit that I was a little in awe of him.

In the following weeks the grief came out on social media. Photos of Jim appearing from everywhere. Stories shared. He never used it himself. A self confessed technophobe who never really got the “interweb”. I couldn’t find a photograph of the two of us. I looked through other peoples Facebook albums but nothing there either. I was heartbroken to realise that one didn’t exist. I realised there’s a lot of my good friends I don’t have photos with. I see people taking photos together when I’m walking around London or eating my lunch by Thames. Tourists with selfie-sticks, couples and friends. They seem to get judged and called narcissistic. I don’t get it myself. What’s wrong with taking photos with your friends? You never know when one might be gone.

As the months passed by I found myself cooking big meals for people a lot more. I’ve always liked making curries or pasta dishes. I never liked cooking roasts or baking things. I’d always preferred to experiment with spices and create sauces. The timings and exactness of cooking a roast dinner or following a recipe would stress me out. But I soon found myself taking any opportunity to roast some meat, prepare some vegetables and cook for a group of people. I’d invite friends to my flat in South London or to my Mum’s house in Sheffield whenever I was back home and had an oven to play with. I was there for a while last September and invited people over each Sunday for a big dinner. I had a family gathering one day and slow roasted a pork shoulder for seven hours. The crackling was crisp and when I cut the string around it the meat fell apart perfectly.

Then I found that roll of film. As I looked at that photograph, the finished plate of food with Jim’s figure in the background, It dawned on me that without thinking about it I’d been honouring him in the kitchen. A method of cooking that used to stress me out had become a thing of joy. Mastering the timing to perfectly roast a joint, or to pan fry a steak to the exact second for tender perfection. It’s not the task that’s the joy but the final product. Not the food, but the satisfaction of the recipients. The simple pleasure of cooking something wonderful for the people that you love.

Now whenever I’m cooking something special. Roasting meat, preparing potatoes or frying good steaks in a red hot pan, my eyes on the second counter determined to get it right. I always think of Jim Disney, with his beard and long curly locks. Bumbling around the kitchen in his dressing gown, looking like a mini hairy Jesus.